electronic journal of contemporary japanese studies

Article

3 in 2011

First

published in ejcjs

on

31

May

2011

Radio and Television Consumption in Japan

A Trilateral Intercultural Comparison with the UK and Germany

By

Ulrich Heinze

Lecturer

in Contemporary Japanese Visual Media

Sainsbury

Institute for the Study of Japanese Arts and Cultures (SISJAC)

Centre

for Japanese Studies

University of East Anglia

About the Author

Abstract

This article explores Japanese radio and television ratings and compares them to those in Britain and Germany. This macro-perspective on media consumption identifies culture-bound habits in Japan and Europe and refutes the expectation of a global merging of media content. Theoretically, the argument follows Yoshimi Shunya's concept of the 'national timetable' of television use in Japan, and empirically it underpins Takahashi Toshie's ethnographic field study of the Japanese audience. The findings in this article show only a very slow transformation of the Japanese uchi (household), with new and global media stabilising the 'protective cocoon' of the household. The study reveals a considerable dominance of television over radio, and significant differences in media use on the basis of sex and age among Japanese consumers. In contrast to Japan, the daily flows of media ratings reveal similarities between the UK and Germany. The article concludes that consumption habits retain their own national characteristics in the global media age. On the basis of these results, further topics for audience research are identified.

Key Words

mass media; Japan; audience research; radio and television ratings; intercultural comparison

Introduction: Comparative Research Design for the Global Audience

In a globalised world, pictures, images, sound and data circulate across national boundaries even more effectively than passengers or freight containers. Radio and television, as mass media, are enhancing the globalisation process, with information, news, genres and images spreading rapidly around the world. However, this digital acceleration does not automatically entail a global convergence of the many national media systems involved. Instead, they remain bound up by language and culture and retain national characteristics.

Japan is doubtlessly an important hub in this global media network, importing and exporting all kinds of media: films, television serials, videogames, J-pop and manga. However, the international trade in media products also requires their continual adaptation, which goes far beyond simple language translation. When Japanese manga panels reached the West for the first time, they were flipped so that they could be read from left to right. Covers for the American market were always produced by an American artist to offer a familiar visual identity for readers. Today, covers are still designed individually for every country and then approved by the original publisher in Tokyo. Japanese anime undergo similar alterations for the western market, for example many are re-framed to cut out the appearance of Chinese characters, or kanji. This process even happens to American celebrities such as Arnold Schwarzenegger, Harrison Ford and Tommy Lee Jones, who have all appeared in Japanese television commercials. These commercials show a very different side to these celebrities and would be potentially very embarrassing if the commercials were shown to their fans back in America. Sofia Coppola's film Lost in Translation (2003) uses this idea as part of the narrative, for humorous effect. Just as Japanese advertisements are aimed at a Japanese domestic audience, Hollywood is also a closed shop, frequently resorting to remakes (instead of imports) of Japanese horror films for the American audience. Another example is the recent French film adaptation of Taniguchi Jirō's manga Haruka na machi he (2005), entitled Quartier Lointain (2010) and directed by Sam Garbarski. The film depicts a salaryman's literal return to his teenage years during a midlife crisis and has been entirely relocated from the city of Kurayoshi to a small village in France.

However, culture-bound media consumption goes far beyond media content, genres or narrative patterns. It is effective already on the level of media use and consumption style, i.e. in the context of the everyday life of the audience. Especially in the social field of Japan, media and audience studies have confirmed a culture-bound or even national use of radio and television throughout the post-war period (Chun 2007: 72, 224; Yoshimi 1999: 160, Plitsch-Kussmaul 1995: 212, 346). Japanese media theorist Yoshimi Shunya has even allocated the function of 'national medium' to television in Japan, rather than film, during the period of high economic growth. He described the function of television as a device which has structured daily life in Japan since the 1960s and until at least the 1980s. During these decades Japanese television programmes followed a strict pattern of programming with defined 'national time-windows or time-slots' (nashonaru na jikan) for every day of the week. Within these slots, programmers created separate gendered time zones and targeted either the female or male audience with its respective genres and narratives (Yoshimi 2001: 138; 2003: 476-479).

Recent western audience studies have frequently examined the impact of migration, changing gender relations, and new mobile devices on media consumption (Morley 1992, Silverstone 1994, Lull 1995, Ang 1996, Morley 2000, Klinger 2006). For the purpose of this trilateral comparison of media use, only texts focusing on Japan or with a comparative approach (Morley/Robins 1995, Plitsch-Kussmaul 1995, Yoshimi 1999/2001/2003, Furuta 2002, McVeigh 2003, Iwabuchi 2004, Chun 2007, Takahashi 2010) have been thoroughly taken into consideration. This reduction of theoretical complexity was inevitable in order to focus on previous studies about the history and characteristics of Japanese media consumption.

After the collapse of the 'bubble economy' in 1989, Japan was exposed to a rapid globalisation process, accelerated by the Internet. In 1995, Morley and Robins proposed a new discourse of 'Techno-Orientalism', which expressed the western fear of an economically and technologically strong Japanese nation (Morley/Robins 1995: 168, Yoshimi 1999: 152). The national and cultural specificities of the Japanese attitude towards media and technology have continued to attract academic attention.

Today, after two decades of globalisation these national and cultural specificities, economic stagnation, social change, ageing and insecurity, are still conspicuous. While pachinko, manga, the Walkman and the Tamagochi were created in Japan, the Internet, although a global medium, is now being used by Japanese people in different ways to the West. Brian McVeigh points out the correlation between commuting in urbanised Japan and the preference for portable Internet devices, and speaks of an 'atomised individualisation', supported by the media (McVeigh 2003: 28).

Of course, individualisation is a key category to describe postmodern societies around the globe, and is intrinsically connected to media use. Barbara Klinger has recently argued that the range of available home media today help to create a 'Fortress of Solitude' and a state of insularity, which is even enhanced by television, the PlayStation and Game Boy (Klinger 2006: 9, 242). As they promise to protect the consumer in his interior space, they both connect and disconnect him, and the public sphere loses its actors. In Japanese modernity, this division of social space has been even more radical than in the West. While the Japanese word for 'public' (kōkyō) has the meaning of 'formal', 'generally available' or 'provided by the state' (e.g. in kōkyōhōsō: public broadcasting), the category of a political public sphere or centre shared by all is mainly perceived as a western (e.g. Habermasian) import. Instead, the distinction between inside and outside, uchi and soto, or honne and tatemae, is still deeply inscribed in Japanese interaction, networking, thinking, and media use.

Consequently, a complement to Klinger's 'fortress' can be found in the field of Japanese audience studies. In her recent field study on the Japanese media audience, ethnographer Takahashi Toshie discovered typical Japanese uchi or secluded households (or 'Lebenswelten', to use a Habermasian term). According to Takahashi, contemporary Japanese consumers still use the mass media to set up a 'protective cocoon' (Takahashi 2010: 139, 164), which lets them escape from insecurity, public life or simply the stress of the outer world. Paradoxically, modern mass media thus helps to maintain the traditional uchi/soto (inside/outside) dimension of Japanese society. They apply digital technology in order to stabilise the traditional Japanese household, uchi or interiority, and their users receive and retain an imaginative space for their self-creation within the global communications network.

This article adds a third, complementary and macrological perspective on radio and television consumption in Japan. Starting from Takahashi's findings, it compares for the first time Japanese radio and television ratings with those in the UK and Germany, in order to identify the differences between national media use. For this purpose, media research data was collected in summer 2010 in Tokyo, London and Hamburg, to allow for a trilateral comparison. A criticism of this kind of rating system is that although they show the number of viewers, they do not show how much attention these viewers are paying to the programmes they watch (Ang 1991: 35, 81; Morley 1992: 177). However the figures for each country have been collected in a similar way so they are comparable and they reveal significant differences between the countries.

In Japan, the NHK Broadcasting Culture Research Institute measures radio and television ratings across the whole of Japan every June and November in representative samples of about 2500 participants using a diary system (NHK 2010). In addition, the company Video Research measures radio ratings using diary questionnaires (nikkishiki) in the capital, Tokyo, within a radius of 35 km around the central station. The company targets almost 3000 persons between 12 and 69 years four times a year (Video Research 2009). In the UK, the so-called RAJAR (Radio Joint Audience Research) interviews are conducted every year over 50 weeks with 114,000 British people. In Germany, six companies question more than 60,000 listeners twice a year. Each 'Media Analysis' lasts about three months (ARD Medien Basisdaten 2010). Although electronic meters have been developed for radio ratings, they are not (yet) in use.

By contrast, television ratings, which are vital to the advertising industry, are measured electronically throughout the year in all three countries. Several companies produce precise individual and household ratings, mainly funded by the private and public broadcasters. Only a small selection is published in the mass media. In Japan, Video Research collects data in 6600 households nationwide. In 3400 households, including 1800 in the metropolitan areas of Kantō, Kansai, and Nagoya, the so-called 'people-meter' (PM) measures viewing data on a daily basis throughout the year (Video Research 2010). In the UK and Germany television ratings are also arrived at through the observation of the viewing habits of a representative panel of over 5000 households across the country. The meters break down the viewers' behaviour to time slots of five minutes (and less) and send them to BARB (Broadcasters' Audience Research Board) in London and to GfK (Gesellschaft für Konsumforschung) in Nuremberg every day (Attentional London 2010, ARD Media Research 2010). For this trilateral comparison, the Japanese radio and television ratings were collected first and then complementary datasets were collected from Attentional London, a registered data processing bureau for BARB, and from ARD Media Research Hamburg. As specified in the figures, the data gathered for radio and television audiences differentiates between age groups and gender, workdays and weekends, as well as metropolitan media use in Tokyo and London. The research methods in all three countries are therefore very similar, and setting aside discussions about the degree of attention the audience pays to media, or the 'intensity' of media consumption, the data stems from representative surveys and can be used as reliable sources for a comparative approach.

All the results of the trilateral comparison of media use confirm culture-bound characteristics and considerable differences between the three countries. In Japan the important specifics of national habits of using media must be sought in the differences a) between both media (radio and television) and their communicative success b) between the habits of male and female consumers and c) between age groups and cohorts. The article concludes that instead of a global convergence or homogenisation, a specifically Japanese hybridisation of visual media use is in progress. Attracted – and distracted – by the Internet and mobile phones, television viewers' wavering preferences will further diversify and challenge audience research. Future comparative research design will therefore have to identify genres and programmes which are popular in at least two countries. Intercultural texts such as globally distributed television serials would then allow for a multilateral approach combining content analysis, ethnographic observation of consumption styles, and the empirical analysis of ratings and questionnaires. Only a more complex methodology will help to understand the reasons for the sustained cultural embedding of media consumption in most countries of today's globalised society.

The Minority Mass Medium: Radio in Japan

In Japan, only a minority regularly listens to the radio, with less than 40 percent of the population listening to the radio at least once a week. In the UK and Germany, people listen to the radio for several hours every day, with the average amount of individual radio minutes per day above 130 and 170 minutes respectively. In Japan however, this number has already fallen to below 40 minutes (Nakano 2009a: 66, 76). Today many Japanese consumers already spend more time reading print media (newspapers, journals, books or manga) or using their mobile phones than listening to radio programmes (Yoshida 2007: 126).

Figure 1 depicts the number of radio minutes consumed individually per day in Japan by age over the past 30 years. With the peaks in consumption shifting gradually to the right since 1979, the graph clearly identifies a 'radio generation'. This cohort, born between 1935 and 1954, includes the Japanese baby-boomers (dankai sedai), born in the immediate postwar period (Shiraishi 2008: 526). There is no obvious structural change in its listening habits over the last decades. This cohort grew up with radio as the dominant mass medium, and has internalised its consumption, preserving the habit of radio listening as it ages. Therefore the maximum of the graph moves with this cohort as they age (Yoshida 2007: 132; Morofuji 2010b: 6). Television in Japan was not launched until 1953 and only reached 20 million viewers or roughly a fifth of the population in 1967. An NHK survey of 1952 found that the Japanese spent an average of about four hours per day listening to the radio (Furuta 2002: 111). As a result this 'radio cohort' could foster its interest in radio and still continues to listen today, at over 60 years of age. At the same time, this group is also facing retirement and will have even more spare time in the near future to listen to the radio. However while these radio veterans are still listening for about an hour every day, the radio clearly fails to attract and retain new consumers from younger generations.

Figure 1: Individual radio minutes/day by age, Japan, 1979 - 2009.

Averages: 1979:42min, 1989:38min, 1999:33min, 2009:33min.

Source: November nationwide surveys, NHK Hōsōkenkyū to chōsa.

The comparison between Japanese and western daily radio minutes by age (figure 2) underpins that the function, meaning and use of radio must be culturally contextualised. Whilst in Germany, radio is just as important as television in terms of daily consumption, the UK audience, although radio use increases with age, consumes radio at a considerably lower level. In Japan, only the elderly reach a considerable level of consumption, although is still far lower than that of similar cohorts in Germany or the UK. In everyday life, radio programmes are mainly broadcast for commuters in cars or trains (idōchū), where earplugs create a minimal feeling of personal (sound) space – something, which is already threatened by visual media, including screens and advertisements. While in Britain and Germany, men listen slightly more than women, this gender gap is far more significant in Tokyo than in London (figure 3). This clearly mirrors Japanese gender roles and the respective worlds of men and women; the business world of the typical sararīman (salaryman) is strictly separated from the domestic space of the traditional housewife (sengyōshufu) with no or only a part-time job and with easy access to television. Still almost half of married women in Japan do not work, and about a quarter of them work part-time. The percentage of the female workforce between 25 and 60 years, in the so-called 'M-curve', therefore oscillates between 60 and 70 percent (men: above 95 percent, Himeoka 2008: 247; Chun 2007: 81, 93). Despite the constantly rising age of marriage and the declining birth rate in Japan, motherhood and regular employment are widely considered mutually exclusive.

Figure 2: Individual radio minutes/day, Japan, UK & Germany, 2010.

Sources: Hirata 2010, Attentional London, ARD Media Research (data for 2009).

Figure 3: Individual radio minutes/day by gender, Tokyo & London, 2010.

Sources: Video Research Tokyo, Attentional London.

Figure 4 confirms the considerable cultural differences in radio use both between Japan and the West, and between western countries. It depicts the daily flow of individual radio ratings in all three countries. While in Japan, the radio is only a minority medium with consistently low ratings over the day; the ratings reach a significant peak in both European countries in the early morning between 8 and 10am. While the German ratings then gradually decrease over the day, the UK figures start to rise again between 3 and 5pm. They then remain above the German level over the rest of the day. This rise is measurable in all age groups and needs a more careful examination of UK listening habits in a separate study (figure 6).

Figure 4: Daily flow of individual radio ratings, Japan, UK & Germany, 2010.

Sources: Video Research Tokyo (data for April 2010), Attentional London (data for Q2 2010), ARD Media Research (data for 2009).

In Japan, there is an important difference in radio listening between metropolitan Tokyo and the nationwide average. In the segment of the elderly (above 60 years of age), the measurement in Tokyo (by Video Research) is approximately 100 minutes, which is more than twice as high as the figures for the whole of Japan (by NHK). One of the reasons is certainly the high number of radio programmes available in Tokyo (six AM and six FM stations). Interestingly, this gap in radio consumption between the capital and the countryside is also visible in television ratings, although on a much smaller scale. However, even in Tokyo the emergence of new media will further intensify the pressure on traditional radio programmes.

To illustrate the different concepts of radio in Tokyo and London, figures 5 and 6 compare the daily flow of radio ratings in both capitals by age (nensōbetsu). The figures reveal two entirely incompatible patterns of daily radio use. In both cities, there is a conspicuous age hierarchy, with the elderly at the top of the graph, consuming most and the teenage listeners at the bottom of the graph, consuming least. This confirms the average radio minutes by age, as depicted in figure 2. In London, the radio ratings reach a peak at around 8am, and then the figures for almost all cohorts decrease until 3pm. They recover in all segments from 3 to 5pm and then fall below 10 percent after 8pm in the evening (figure 6). This timeslot is widely reserved for television viewing. In Tokyo, the gender gap is much more significant (figure 5) and there are only a very few male listeners younger than 35 or female listeners younger than 49 years old. The ratings reach their peak at 10am; this so-called 'golden time' is the only period, where radio ratings are temporarily higher than those of television. In this time slot on workdays, TBS (on AM 954 kHz) as the most successful radio station in Tokyo broadcasts its morning show Yūyūwaido from 8.30am to 1pm with the popular presenter Osawa Yūri (b. 1941). He has worked on the show for many years, already presenting it more than 6000 times. Instead of music, the show is mainly composed of interviews, gossip, and public service announcements such as weather reports and traffic information for commuters. However, it loses many listeners after 11am. At noon, when private television broadcasters present their daily soaps, radio ratings drop sharply (figure 5). They then recover until 4pm, when even loyal listeners start to switch off in favour of television. At night, only some elderly people keep listening, with popular programmes including the NHK news as well as the traditional Japanese comedy genres rakugo and manzai

Figure 5: Daily flow of radio ratings by age and sex, Tokyo, 2010.

Source: Video Research Tokyo (data for April 2010).

Figure 6: Daily flow of radio ratings by age, London, 2010.

Source: Attentional London (data for Q2 2010).

The decline of the radio audience in Japan is measurable year-on-year. The comparison of the Tokyo radio ratings over the day by age between 2002 and 2008 (figures 7 and 8) demonstrates dramatic changes and the loss of listeners in six years. Ratings have dropped in all cohorts without exception (the elderly above 60 years were not yet observed in 2002 and are therefore not shown in either figure). The age hierarchy is almost complete throughout the day. In 2002, there was still a specific time slot for teenage listeners. High school pupils in particular used to switch on the radio after 10pm, after returning home late from school and using the radio as a distraction while studying or doing homework. Broadcasters directly targeted them with specific music programmes and young presenters. But within six years this kind of early night youth radio has almost disappeared (Yoshida 2007: 131). One of the reasons is certainly the success of visual and digital media. Already mobile phones claim about 30 minutes and the Internet about 60 minutes every day for an average teenager, and this is replacing traditional radio listening (Nakano 2008: 185, 194).

Figure 7: Daily flow of radio ratings (listeners only) by age in Tokyo, February 2002.

Source : Video Research Tokyo.

Figure 8: Daily flow of radio ratings (listeners only) by age in Tokyo, April 2008.

Source: Video Research Tokyo.

Radio in Japan is therefore facing a potentially serious fate. Although there may still be some limited time slots for loyal listeners, especially for people interested in news, sports, or old-style Japanese pop-music (e.g. Hiru no kayōkyoku at noon on NHK2), the medium is not attracting younger listeners and will not survive without technical, digital or visual enhancements. However adapting to current developments in the media world would seriously affect radio's identity and integrity. Today – especially in Japan – television is fulfilling a similar function to radio as a 'talking wallpaper' (kabegami) for many hours of the day.

The Japanese TV Audience: Differences by Gender and Age

In the three countries being compared, the average individual consumes more than three hours of television every day. Unlike German children, those in the UK and Japan almost reach this level at a very early age. Like radio consumption, television consumption increases with age (figures 9a-c). Depending upon the age groups included in the measurements, the numbers of daily television minutes can reach 193 minutes in Germany (2009: 10y-) and even 225 minutes in the UK (2009: 14y-). In Japan, the NHK survey recorded 235 minutes (November 2009: 7y-) across the whole of Japan, while Video Research recorded 249 minutes (2009: 4y-) in the Tokyo Metropolitan Area. Daily television use in Tokyo reaches up to six hours per day in the elderly age group. However the elderly in Europe also frequently spend half of their waking time in the consumption of different mass media.

Figure 9a-c: TV minutes/day in Tokyo, London, Germany, 2009.

Sources: Video Research Tokyo, Attentional London, ARD Media Research.

The gender gap in media use is at its most significant in Tokyo (figure 9a). The reason lies again in Japanese gender roles and separated spaces. Most housewives can view television shows and serials during the day, which means that women between 30 and 50 years of age watch much more television than their husbands or partners. The gender gap in the UK is smaller, but also clearly measurable in all age groups (figure 9b). German research draws the main distinction between East and West (figure 9c). This cultural gap is more significant than the gender gap, and almost all demographic and economic statistics (e.g. birth or growth rates) suggest this comparison, which is also facilitated by the federal structure of the country. The media consumption data shows that television ratings in Eastern Germany are about 15 percent higher than in the West, partly because of doubled unemployment rates.

In Japan, for every minute of radio consumed, five minutes of television are consumed. In the average household the television is on for about eight hours every day. For this reason, it is important to look beyond the ratings for individual consumers or (specific) media. Television viewing is of course often shared with others or combined with other activities. While men tend to clearly distinguish between work and leisure, women often sew, iron or chat in front of the television. About a third of all television minutes are dedicated to other such activities (Nakano 2009b: 44). The screen then fulfils the function of a coloured and talking wallpaper. In addition, the inclination to watch alone, without partner or family members, is constantly growing (Hara 2007: 156; Nakano 2008: 196; Morofuji 2010a: 4).

Since the significant gender difference in the Japanese ratings mirrors gender roles in daily activities, it is not visible in teenagers' television viewing and this gender difference also disappears in the cohort of elderly and retired people. The time spent viewing television increases with age and with the ageing of society. Japanese viewers above 60 years of age already spend more than five hours in front of the television screen. Surprisingly, the Internet does not directly compete with television (Shiraishi 2008: 523). Television creates a high degree of relaxation for users between 20 and 40 years of age (Nakano 2009b: 52), but the number of available programmes and competing media (telephone and the Internet) also reduces the amount of attention viewers pay, as well as affecting their concentration. Therefore consumers don't automatically like television programmes more just because they watch more. Likewise, growing material wealth does not always entail a higher degree of satisfaction or joy.

The daily flow of individual television ratings in all three countries shows considerable differences in the distribution of television time, although only until the early afternoon. From then on the ratings are remarkably similar (figure 10). The typical Japanese morning and noon peaks do not appear in Germany and the UK. The UK audience watches more than the Germans only in the five hours before noon (in contrast to radio use, see figure 4). In the afternoon, the UK figures remain slightly below the German level. Again, the precise reasons for these discrepancies are unclear and would require further scrutiny. In the UK and Germany, radio attracts more consumers than television until at least 4pm, while in Japan the television is clearly prevailing throughout the day - except for the short 'golden time' from 10 to 12pm. In contrast to Europe, Japanese television ratings reach three daily peaks, at 8am and at noon (for the popular television serials), as well as in the evening at around 9pm. Therefore, these television ratings must be examined more carefully in the next step, examining different age cohorts, by sex (danjonensōbetsu), and viewing on weekdays only.

Figure 10: Daily flow of TV ratings over workdays in Japan, UK & Germany, 2009.

Sources: Video Research Tokyo, Attentional London, ARD Media Research.

Comparing the television consumption of children in Japan and Britain (figure 11: 4-12 years, this cohort is not yet measured in Germany), it can be seen how Japanese consumption patterns are acquired at an early age. The two peaks at 7am and 7pm reflect viewers' habits, which they will maintain for the rest of their lives. In contrast, British children, who also have a specified television time slot in the morning at 8am, seem to loose this habit when they become teenagers and the peak at 8am almost disappears (figure 12). Many will probably switch over to radio, but the reasons why teenagers and children in Japan have such a similar pattern of consumption, while these age groups in the UK differ significantly is unclear and would need further field research. It is surprising that Japanese children and teenagers dedicate their evening hours to the television earlier and much more radically than the Europeans.

Figure 11: Daily flow of TV ratings over workdays for children and teenagers. Japan & UK, 2009.

Sources: Video Research Tokyo, Attentional London, ARD Media Research.

Figure 12: Daily flow of TV ratings over workdays for teenagers in Japan, UK & Germany, 2009.

Sources: Video Research Tokyo, Attentional London, ARD Media Research.

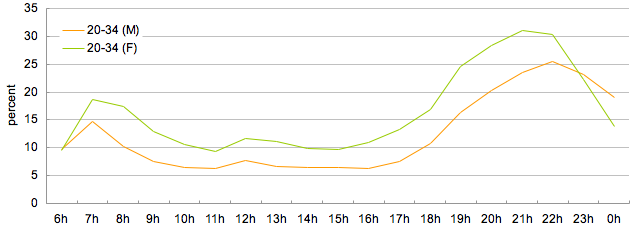

The time that young adults between 20 and 34 years of age spend watching television stagnates. The 20 to 34 age group watches no more than teenagers in Japan, quite in contrast to their western comparators (figures 9a-c). However, they slightly reschedule their consumption time around the first two peaks of the general television rating over the day, and prefer different media in the evening (figures 13 and 14). This development is especially visible among adults without children, who spend more time outside the home. They prefer the Internet or listening to music and also invest more time selecting the media they consume. They tend to switch on the television as soon as they arrive home (toriaezutsuke), but they also frequently zap the channels with their remote control (rimokonkirikae). In addition they also record many programmes in order to watch them at a later time, when they can concentrate on them more.

Figure 13: Daily flow of TV ratings over workdays for young adults in Japan, 2009.

Sources: Video Research Tokyo, Attentional London, ARD Media Research.

Figure 14: Daily flow of TV ratings over workdays for young adults, UK & Germany, 2009.

Sources: Video Research Tokyo, Attentional London, ARD Media Research.

In her study on the viewing habits of adults without children on Mondays Morofuji Emi (2009) distinguishes between three groups: the 'TV lovers' (terebi suki), the 'cool viewers' (kankyōteki), and the 'less interested' (kihaku). The first two groups have a positive attitude towards media and their entertainment, and enjoy them until late at night. The 'less interested', however, work until late and do not have much spare time to consume media. They switch off soon and then read print media or just go to bed early (Morofuji 2009: 51). Both in Japan and the UK, there is a considerable gender gap in the ratings of young adults over the entire day. The British watch considerably more in this age group, and the peak of their ratings is up to 10 percent higher than the Japanese one. Also the peaks in Japanese ratings in the morning and at noon are now clearly established and have no comparator in western countries. Western viewers tend to switch off an hour earlier than the Japanese, many of whom will then catch-up on their sleep on commuter trains or in business meetings.

All these typical characteristics of Japanese television consumption become even more evident in the ratings of adults between 35 and 49 years of age (figure 15). The gender gap reaches its maximum, and female viewers clearly occupy the time slots at 7am and at noon for their daily soaps and serials. The curve for female viewers is nearly as high at 7am (40 percent) as in the evening (45 percent). This 'gender order' (seichitsujo) in the field of media use was confirmed by Saitō Kensaku's recent study on the morning viewing habits of sixteen Japanese housewives and mothers between 30 and 59 years. He found both habitual and fractional (bubunteki or 'zapping-based') viewing styles, mostly combined with household duties (Saitō 2011: 41, 47). While the television in the morning serves as a clock and a traffic-and-weather-information-box, many women also have programme layouts in mind and know the best time slots to switch to the next channel. In contrast, the gender gap in the adult age group is narrowing in the UK (from 40/30 percent to 45/40 percent at primetime), as is the discrepancy between the UK and Germany (figure 16). The similarity between the ratings in these two countries in this segment is just as striking as the structural difference between Europe and Japan.

Figure 15: Daily flow of TV ratings over workdays for adults, Japan, 2009.

Sources: Video Research Tokyo, Attentional London, ARD Media Research.

Figure 16: Daily flow of TV ratings over workdays for adults, UK & Germany.

Sources: Video Research Tokyo, Attentional London, ARD Media Research.

In the segment of viewers above 50 years of age (figures 17 and 18), there is no more structural change in television use. Since these viewers watch more, all three peaks rise too: from 40/20 to 40/30 percent, from 16/7 to 30/23 percent, and from 45/30 to 60/50 percent. Japanese women even extend their intensive viewing in the morning until 8am, due to the popular NHK morning dramas, which usually feature female heroines. While the Japanese gender gap shrinks, the gender gap in the UK remains stable. With the rapid ageing of all industrial societies, the future development of the media use of the 'silver generation' has become an important research area (Shiraishi 2008: 513). While Japanese women extend their viewing time gradually over their lifetime, Japanese men tend to do so abruptly after retirement. Supporting factors range from depression, insecurity, boredom, dissatisfaction, but also social integration and stability. Those who embrace television viewing in old age have not necessarily been ardent viewers earlier in their lives. On the contrary, this group of passionate viewers also often has a traditional attitude to leisure activities. They have many friends with whom they can talk face-to-face, they reject contemporary entertainment shows on television and they prefer the radio, particularly shows such as the news on the public broadcaster NHK (Saitō 2008a: 17).

Figure 17: Daily flow of TV ratings over workdays for older adults, Japan, 2009.

Sources: Video Research Tokyo, Attentional London, ARD Media Research.

Figure 18: Daily flow of TV ratings over workdays for older adults, UK & Germany, 2009.

Sources: Video Research Tokyo, Attentional London, ARD Media Research.

With the Japanese baby-boomers (dankai sedai born 1945-50) reaching retirement age in the next five years, male television viewers in particular will increase the time they allocate to television. Therefore the traditional order of phases in the life of the media consumer (raising children à grown-up children become adults and leave à older couple uses different television sets in different rooms and à learns to select and enjoy different programmes, Saitō 2008b: 79) will change. It is already today undermined by the use of several television sets (or soon computers with digital broadcasting receivers) in the majority of Japanese households. All these innovations lead to the question; what will viewers watch? The changing attitudes of older people are difficult to measure, and their interests and needs are multiple and complex, as is the supply of media programmes. What can be said is that apart from consuming media for distraction and relaxation, older people have a strong inclination towards learning, i.e. they prefer language courses and documentaries, and they appreciate shorter and more understandable explanations. Commercial broadcasters specialising in infotainment will therefore gain a greater share of their growing viewing budget than the public broadcaster NHK.

Discussion and Conclusion

This article has carried out a trilateral comparison of radio and television ratings in order to identify the main characteristics of media use in Japan. As expected, there are already important discrepancies between the UK and Germany, but even greater differences between Europe and Japan. These are:

a) the quantitative domination of television over radio in Japan, in contrast to a rather more balanced use of both media in the UK and Germany. Apart from the cohort of older listeners, who are now in their 60s, television has almost replaced radio in Japan. The main reason for this is the early introduction of morning television programmes from 1956 onward. In 1961, NHK defined the time slot for television serials for women at 8am with the famous serial Musume to watashi (My daughter and I, Furuta 2002: 150, 158; Yoshimi 2003: 478). This time slot is still reserved for television serials in Japan today. In the UK and in Germany, so-called 'breakfast television' was only introduced in the 1980s, which allowed the radio to defend its position as the leading medium until deep into the afternoon.

b) the considerable gender gap in Japan; radio attracts more male listeners, while television mainly more female viewers, which corresponds to gender roles and the gendered structure of daily work and life. This gender gap, which is also significant over the entire day in the UK, obviously echoes the strict 'gender divide' in the Japanese workforce. The narrowing of this gap is today further delayed by the ongoing economic crisis and fierce competition for permanent positions (Shire 2008: 965, 972). In this environment, the stereotype of the traditional Japanese housewife (sengyōshufu) is changing only slowly.

c) the differences in media use between population cohorts in Japan; media consumption increases with age in all three countries, but the increase is most significant – and abrupt – in Japan. The reason lies in the rapidly ageing society, where younger cohorts are widely seduced by new mobile media and the Internet, or simply have no children (yet) and go out more frequently. In contrast, older people today have enjoyed a successful work life in a growing economy. Slightly reluctant to use new media or the Internet, they instead extend their television consumption, especially after retirement, and they remain convinced of the leading role of television in the media landscape (Morofuji 2010b, 20).

The trilateral comparison carried out here concludes that the growing globalisation, hybridisation and complexity of the media landscape have not changed the national characteristics of media consumption. In particular the data from Japan underpins the opposite conclusion, that the process of 'transforming the traditional uchi into a more modern uchi' (Takahashi 2010: 136) is very slow. Important characteristics of media use in Japan related to gender roles, which media researchers have observed in the first two decades of television culture (Chun 2007: 308), can still be empirically confirmed today. Television is clearly the leading national mass medium in Japan, by far outperforming radio, which today struggles for younger listeners. The Japanese audience acquires its viewing habits at an early age, and the typical peaks of Japanese ratings can already be seen in the segments of children and teenagers. The typical Japanese television rating figures reach three peaks per day, and among adult viewers it mainly attracts women, who enjoy special time slots in the morning and at noon. However, this gender difference gradually disappears in the segment of the elderly.

From these findings, three important research topics can be derived. Firstly, the historic phase from the 1950s to the1960s, when television in Japan started to replace radio as the dominant mass medium, must be examined more closely with a survey, which exclusively targets the (now) elderly listeners, who experienced this change. The retrospective question is how, why, and to what extent they changed their habits. Secondly, the significant gender difference in media use in Japan today requires further scrutiny. Considering Japanese politics on gender equality, the growing reluctance of young women to lead the traditional life of a housewife and rising divorce rates, the reasons for this gendering of television use as well as programmes targeting only one half of the audience need to be carefully examined. In addition, a comparison of the consumption habits of married housewives with those of single women would deepen our understanding of the Japanese 'gender order'.

Thirdly, there are changes in Japanese media use, which are not reflected in the ratings presented in this article. Besides the issue of an ageing audience, there are important changes taking place in the media landscape itself, those of digitalisation, globalisation, and diversification. The new Tokyo Sky Tree and the digital 'switchover' in July 2011 are important symbols of this in Japan. The media, especially visual media, is merging, and the time available for the 'hybrid consumption' of videogames, mobile phones and the Internet has been increasing for years (Mitsuya 2002: 20; Nakano 2008: 198). For Japanese consumers these technologies have practically become a 'part of the[ir] body' (Takahashi 2010: 179). Already today young adults (20-30 years of age) in Japan are using these new media more often than the more traditional television and mobile phones more often than radio. Therefore viewing quality, too, is diminishing. Viewers use several screens simultaneously, and they often combine muted television programmes with Twitter or the telephone (Miura 2010: 93). More and more viewers join the network, but they consume individually and are exposed to even more media at the same time. And it is precisely this shrinking intensity of television viewing that cannot yet be measured or quantified by any of the available methods.

What Takahashi has called the 'modernisation of uchi' in her ethnographic study, is connected to new and portable multiple media supplies, preferred by the younger generation (Morofuji 2010b: 6, 14). McVeigh found evidence of a radical 'atomisation' and 'interiority' in the use of mobile phones, dividing the audience into small units. In particular, the Internet's global network creates an even more stable 'protective cocoon', an interiority that is underpinned by media within the culture-bound patterns of life and consumption. The intercultural comparison of overall television and radio ratings, as carried out in this article, can therefore only be the first step towards more complete research on discrete programmes, which globally attract specialised fan-groups. Such research should target specific genres or programmes, which have been broadcast in at least two countries, and then combine ethnographic audience research on the practice of viewing with empirical comparisons of individual ratings by age and sex.

Appropriate objects would be globally successful American television serials such as CSI or Ugly Betty, which have both been broadcast in Japan. A survey among Japanese viewers of Ugly Betty has already revealed interesting reasons for the show's popularity in Japan. The viewers praised the actors for their skills, voiced approval of the show's view on human relations and emotions, and they liked the focus on guest stars and marginal roles. Surprisingly, they also welcomed the fact that the main character was not just a beautiful heroine (bijin), as well as the general optimism and (uncommon in Japan) its use of happy endings (Miura 2009: 86-88). However, only a more sophisticated and multi-layered research design, which combines surveys, rating analysis and ethnographic observation, promises to break the 'protective cocoon' of the lonely crowd, stuck in front of the television and computer screen.

References

Ang, Ien, 1991. Desperately Seeking the Audience. London: Routledge.

Ang, Ien, 1996. Living Room Wars: Rethinking Media Audiences for a Postmodern World. London: Routledge.

ARD Medien Basisdaten: www.ard.de/intern/basisdaten. [Accessed 17 November 2010].

ARD Media Research Hamburg: Interview and data collection on 13 October 2010.

Attentional London: Interview and data collection on 30 September 2010.

Chun, Jayson Makoto, 2007. 'A Nation of a Hundred Million Idiots'? A Social History of Japanese Television, 1953-1973. London: Routledge.

Furuta, Hisateru, ed., 2002. Broadcasting in Japan: The Twentieth Century Journey from Radio to Multimedia. Tokyo: NHK.

Hara, Miwako / Terui, Daisuke, 2007. Growing Internet Use and TV Viewing Patterns. From 'The Japanese and Television, 2005' Survey. In: Yokoyama, Shigeru (ed.). NHK Broadcasting Studies 2006-2007. Tokyo: NHK Broadcasting Culture Research Institute, 143-158.

Himeoka, Toshiko, 2008. Changes in Family Structure. In: Coulmas, Florian/Conrad, Harald, eds. The Demographic Challenge. A Handbook About Japan. Leiden: Brill, 235-253.

Hirata, Akihiro / Tsukamoto, Kyōko / Sekine, Chie / Watanabe, Yōko, 2010. Terebi, rajio, shichō no genkyō [The Present State of TV Viewing and Radio Listening. From the June 2010 Nationwide Survey on Individual Audience Ratings]. Hōsōkenkyū to chōsa [The NHK Monthly Report on Broadcasting Research], 9, 14-25.

Iwabuchi, Kōichi, ed., 2004. Feeling Asian Modernities. Transnational Consumption of Japanese TV Dramas. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

Klinger, Barbara, 2006. Beyond the multiplex. Cinema, new technologies, and the home. University of California Press: Berkeley.

Lost in Translation, 2003. Film. Directed by Sofia Coppola. USA: Focus Features.

Lull, James, 1995. Media, Communication, Culture. A Global Approach. Cambridge: Polity Press.

McVeigh, Brian J., 2003. Individualization, individuality, interiority, and the Internet. In: Gottlieb, Nanette/McLelland, Mark, eds. Japanese Cybercultures. London: Routledge, 19-33.

Mitsuya, Keiko / Aramaki, Hiroshi / Nakano, Sachiko, 2002. Hirogaru intānetto, shikashi terebi to wa daisa [IT Use Increases but with Lags Far Behind TV: From the Survey on Time Use in the IT Age]. Hōsōkenkyū to chōsa [The NHK Monthly Report on Broadcasting Research], 4, 2-21.

Miura, Motoi / Kobayashi, Kenichi, 2009. Shichōsha wa doko ni iru ka [Where is the audience? Analysis of Ugly Betty Viewers]. Hōsōkenkyū to chōsa [The NHK Monthly Report on Broadcasting Research], 4, 82-99.

Miura, Motoi / Kobayashi, Kenichi, 2010. Terebi no mikata ga kawaru. Tsuittā no riyōkōdō ni kansuru chōsa [TV Viewing is About to Change. From a Survey on the Use of Twitter]. Hōsōkenkyū to chōsa [The NHK Monthly Report on Broadcasting Research], 8, 82-97.

Morley, David, 1992. Television, Audiences and Cultural Studies. London: Routledge.

Morley, David / Robins, Kevin, 1995. Spaces of Identity. Global Media, Electronic Landscapes and Cultural Boundaries. London: Routledge.

Morley, David, 2000. Home Territories. Media, mobility and identity. London: Routledge.

Morofuji, Emi, 2009. Terebi no mukiaikata-betsu ni miru. 20, 30-dai no shichōshazō [Images of Viewers in Their Twenties and Thirties According to the Level of Engagement in Television. From the Time Use Survey on Television and Moods]. Hōsōkenkyū to chōsa [The NHK Monthly Report on Broadcasting Research], 8, 46-53.

Morofuji, Emi / Hirata, Akihiro / Aramaki, Hiroshi, 2010a. Terebi shichō to media riyō no genzai (1) [The Present State of TV Viewing and Media Use (Part 1)]. Hōsōkenkyū to chōsa [The NHK Monthly Report on Broadcasting Research], 8, 2-29.

Morofuji, Emi / Hirata, Akihiro / Aramaki, Hiroshi, 2010b. Terebi shichō to media riyō no genzai (2) [The Present State of TV Viewing and Media Use (Part 2)]. Hōsōkenkyū to chōsa [The NHK Monthly Report on Broadcasting Research], 10, 2-27.

Nakano, Sachiko / Watanabe, Yōko, 2008. Rapid Growth of Internet Use. From the Time Use Survey in the IT Age, 2006. In: Kodaira, Sachiko, ed. NHK Broadcasting Studies 2008. Tokyo: NHK Broadcasting Culture Research Institute, 175-203.

Nakano, Sachiko / Miyamoto, Katsumi / Yoshifuji, Masayo, 2009a. Terebi, rajio shichō no genkyō [The Present state of TV Viewing and Radio Listening. From the June 2009 Nationwide Survey on Individual Audience Ratings]. Hōsōkenkyū to chōsa [The NHK Monthly Report on Broadcasting Research], 9, 66-77.

Nakano, Sachiko / Kobayashi, Toshikuki / Morofuji, Emi, 2009b. Terebi wa hoka no media ijō ni 'rirakkusu' [TV as the Most 'Relaxing' Medium. From the Time Use Survey on Television and Moods]. Hōsōkenkyū to chōsa [The NHK Monthly Report on Broadcasting Research], 4, 40-59.

NHK Broadcasting Culture Research Institute: Interview and data collection on 25 June 2009 and 28 June 2010.

Plitsch-Kussmaul, Kirsten, 1995. Die Entstehung und Ausprägung der Mediensysteme in Japan und der Bundesrepublik Deutschland: Ein Strukturvergleich 1945-1990 [The emergence of mass media systems in Japan and the Federal Republic of Germany: A structural comparison 1945-1990]. Neuried: Ars Una.

Quartier Lointain, 2010. Film. Directed by Sam Garbarski. France: Archipel 35.

Saitō, Kensaku, 2008a. Kōreisha no terebishichō. Shichō ga zōdai suru hito, shinai hito [TV Viewing Among Elderly People (1/2). Some Increasing Viewing Time and Others Remaining Stationary]. Hōsōkenkyū to chōsa [The NHK Monthly Report on Broadcasting Research], 9, 2-17.

Saitō, Kensaku, 2008b. Kōreisha no terebishichō. Shichōzōdai de kawaru koto, kawaranai koto [TV Viewing Among Elderly People (2/2). What Changes and What Stays the Same as TV Viewing Time Increases]. Hōsōkenkyū to chōsa [The NHK Monthly Report on Broadcasting Research], 10, 66-79.

Saitō, Kensaku, 2011. Shichōsha wa asa donoyō ni terebi o mite iru no ka. Shūfu ni taisuru depusu intābyūchōsa yori [How Viewers Watch Television in the Morning. From an In-depth Survey of Housewives]. Hōsōkenkyū to chōsa [The NHK Monthly Report on Broadcasting Research], 1, 30-47.

Shiraishi, Nobuko, 2008. Media Use in The Ageing Society. In: Coulmas, Florian/Conrad, Harald, eds. The Demographic Challenge. A Handbook About Japan. Leiden: Brill, 513-530.

Shire, Karen A., 2008. Gender Dimensions of the Ageing Workforce. In: Coulmas, Florian/Conrad, Harald, eds. The Demographic Challenge. A Handbook About Japan. Leiden: Brill, 963-978.

Silverstone, Roger, 1994. Television and Everyday Life. London: Routledge.

Takahashi, Toshie, 2010. Audience Studies. A Japanese Perspective. London: Routledge.

Video Research Tokyo: Interview and research on 30 June 2009 and 29 June 2010.

Yoshida, Rie/Nakano, Sachiko, 2007. Changes and Trends in Media Use. From the Results of the 2005 Japanese Time Use Survey. In: Yokoyama, Shigeru, ed. NHK Broadcasting Studies 2006-2007. Tokyo: NHK Broadcasting Culture Research Institute, 117-142.

Yoshimi, Shunya, 1999. ‘Made in Japan': the cultural politics of ‘home electrification' in postwar Japan. In: Media, Culture and Society 21, 149-171.

Yoshimi, Shunya, 2001. Nashonaru media no yuragi [The wavering of the national media]. In: Yoshimi, Shunya / Kang, Sang-Jung, eds. Gurōbaruka no enkinhō [Perspectives of Globalisation]. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 119-146.

Yoshimi, Shunya, 2003. Television and nationalism. Historical change in the national domestic TV formation of postwar Japan. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 6, 459-487.

About the Author

Ulrich Heinze is Lecturer in Contemporary Japanese Visual Media at the Sainsbury Institute and the Centre for Japanese Studies, University of East Anglia in Norwich, UK. He is a sociologist specialising in Japanese media studies, intercultural communication and popular culture and gained his PhD in Sociology from Free University Berlin in 1991. From 1992 to 1995 he was Broadcasting Editor at North German Radio (NDR) in Hamburg, and from 1999 to 2005 research and teaching as a postdoctoral Fellow and Assistant Professor at the University of Tokyo. In 2004 he gained a venia legendi (habilitatio) in Sociology from the University of Freiburg. From 2005 to 2006 he received a research fellowship from the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD).

Copyright: Ulrich

Heinze.

This page was created on 31 May 2011.

| |

|

This

website is best viewed with

a screen resolution of 1024x768 pixels and using Microsoft

Internet Explorer or Mozilla

Firefox.

No modifications have been made to the main text of this page

since it was first posted on

ejcjs.

If you have any suggestions for improving or adding to this page

or this site then please e-mail your suggestions to the editor.

If you have any difficulties with this website then please send

an e-mail to the

webmaster.

|

|

|

|